On Bongard problems and the shape of thought

When you first encounter a Bongard problem, it’s a bit like hearing a joke, and everyone but you already knows the punchline. You’re given a set of six images on the left, and another six images on the right, and you’re told that all of the images on the left have something in common, but the images on the right don’t. That’s it. No choices, no hints. You might “pick it up” quickly… or you might not. Either way, it’s on you to figure out: what is the rule?

A Bongard problem.

I’ll leave the solution to this problem at the end of this post. (Hint: the rule is a geometric property that most students are taught around high school.)

I learned about Bongard problems by way of Gödel, Escher, Bach, which traces them back to Mikhail Bongard’s book Pattern Recognition (1970).

I find them interesting because unlike many other puzzles like sudokus and crosswords that are exercises in deduction or memory, Bongard problems are all about induction. Not just applying a pattern, but discovering what the pattern is, and more disturbingly, what it could be. Because, well, the space of possible patterns isn’t finite. It’s more of a function of what ideas you have available to you - your cognitive language, if you will. Your perceptual vocabulary.

In this way, solving a Bongard problem isn’t exactly about getting the “right” answer as it is about aligning your priors with the author’s. Which, if you squint a bit, makes it a little bit like a condensed form of communication. A minimal conversation between minds. (Or maybe just a harder version of I Spy).

If I’ve whet your appetite to try some out, I recommend visiting the Index of Bongard Problems and solving a few. In the remainder of this post, I’ll share some of my own thoughts from my experience solving over a hundred of these problems.

Objects vs relationships

One of the things you begin to realize after attempting a lot of these puzzles is that what you think defines a “rule” or “pattern” can be pretty biased. When you’re trying out rules, you’re trying to abstract the differences of the left images from the right images. You might start by trying to see if images on the left have more triangles, or if they’re more symmetrical, or things like that. But after ruling out different hypotheses, it might turn out that the rule is the shapes on the left touch the border and the ones on the right don’t. Or the shapes on the left are enclosed and the ones on the right aren’t.

These aren’t observations about the actual objects, but rather about the relationships between them, or the frame in which they live.

To me this suggests that the very idea of abstraction isn’t necessarily hierarchical, but rather perspective-oriented. We’re used to thinking of levels of abstraction like object vs group of objects vs scene. But here, most solutions don’t come from decomposing the images into smaller pieces, but rather by applying different lenses. Or by viewing the data through a different set of basis vectors.

Mathematicians understand this intuitively. It’s a lot like the shift when you realize a hairy problem is simpler when it’s modeled recursively, or geometrically, etc. The better representation isn’t the one that’s more detailed, it’s the one where structure becomes visible.

The aesthetics of simplicity

There’s generally an assumption that the images on the left or right should all share some kind of simple feature. But simple to whom? In what representational system? It sounds like it could be ambiguous.

But I think programmers and mathematicians all know the feeling of a solution that feels just right. That’s what it’s trying to capture.

Simple isn’t be a mishmash of several rules, or something totally arbitrary like “shapes made of 17 line segments.” Simple minimizes how many symbols or concepts you’d need to communicate or store the idea in your brain.

Some Bongard problems end up seeming a bit ugly to us because what’s simple isn’t clear-cut or the same to everyone. But some Bongard problems are beautiful - either because they feel inevitable, or because they reveal to you something about the very nature of perception itself. That’s rare.

Can you teach induction?

This is the probably the most interesting pedagogical or AI-related question as it pertains to Bongard problems. Can you train people to be better at induction? Figuring out rules from examples?

The traditional way many subjects are taught at school is through bottom-up instruction. First you learn addition, then subtraction, then multiplication, division, equations, etc. But with Bongard problems, rules don’t get you far. What you need to solve them is better mental flexibility.

Teaching that is hard! To cultivate inductive thinking skills, you need to expose people to ambiguity; give problems that can’t be solved just by following rules. Let them struggle a little, maybe. Not because it builds character or anything, but because it’s important to practice dealing with open-endedness.

But the idea of teaching inductive thinking also applies to computers. Since the dawn of the microchip, computers have been essentially unparalleled at following rules, and figuring out rules automatically was the dreams of researchers for decades. And today, we’re getting there with machine learning.

Bongard problems aren’t quite computer-friendly because the solutions are hard to verify – two humans can come up with different answers to a given problem, and they might agree that both answers are correct. Despite the problems being purely visual, the answers have a language component to them.

But the ARC-AGI benchmark designed by François Chollet is very close to the Bongard problems in spirit:

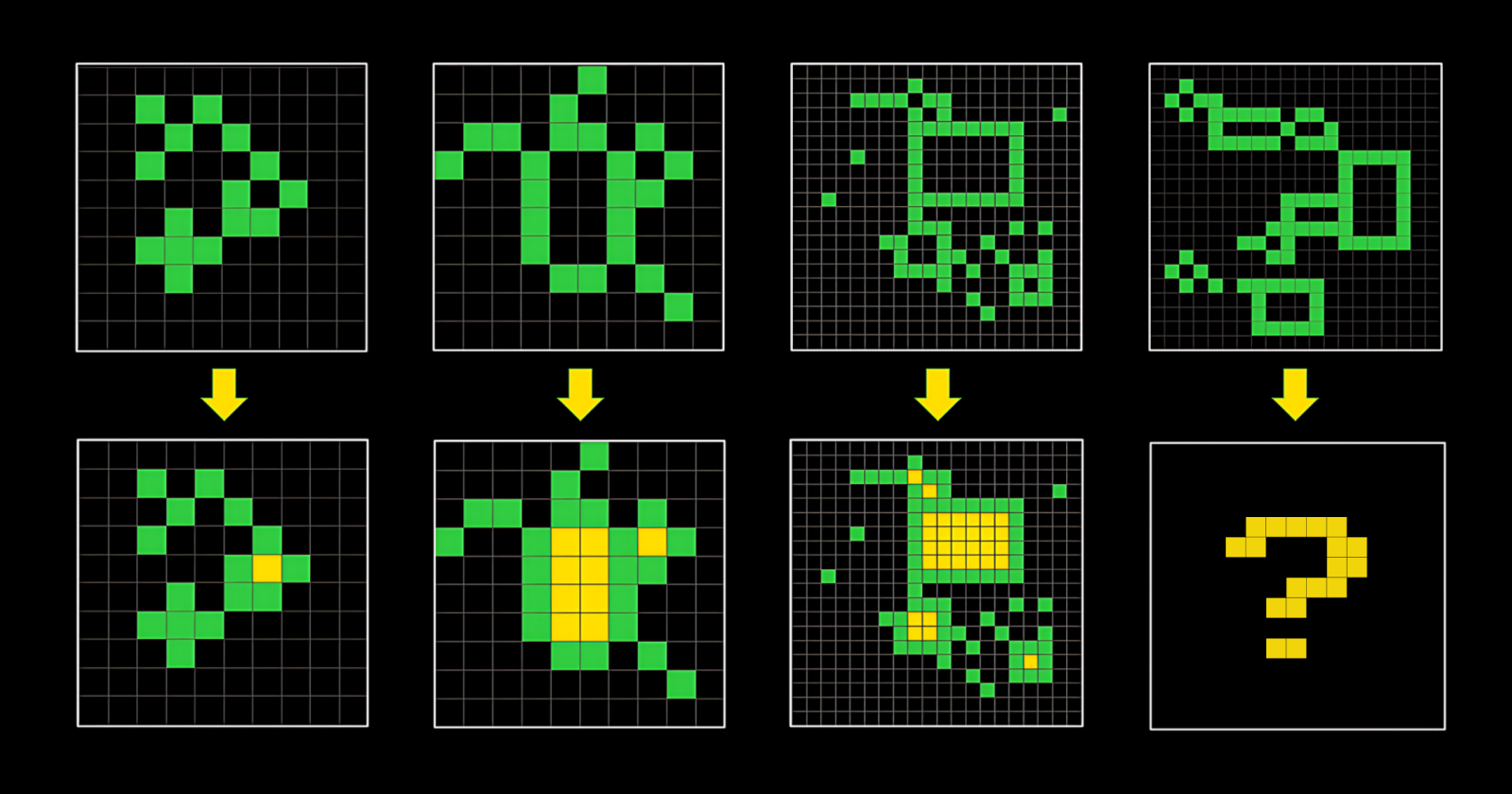

An ARC-AGI task.

In an ARC-AGI task, a sequence of 3-5 input-output pairs of images are given, as well as one additional input image. The objective (for you, or a computer) is to figure out the relationship between the input-output pairs, and produce the correct “output” for one more input. The example above shows a task where the rule is to “fill in the shapes with yellow,” but in practice they can range from applying gravity to a set of objects, to inferring the gap in a symmetric pattern, and so on.

Both games are extremely similar since they rely on your inductive reasoning skills. No set of blunt rules will be able to memorize every possible function. They’re also both visual, which means that the space of possible relationships is also unbounded. The main difference here is that that the “rule” you’re figuring out is more akin to a mathematical function, whereas in a Bongard problem the rule more like a categorization.

Back in 2019, when the first version of the ARC-AGI benchmark came out, it seemed like no computer programs could reliably solve the problems with more than a 30% accuracy. But with recent developments, and models can routinely solve it with over 75% accuracy. A new ARC-AGI-2 benchmark has since been created that intends to up the ante, but only time will tell how soon this challenge will be cracked.

Conclusion

If you’re interested in building powerful AI, you should check out Bongard problems. As tiny and artificial as they are, I think they give us a glimpse into what makes human reasoning so difficult to reproduce. There are all kinds of cognitive processes we take on as humans, but one of the most essential ones is making judgements with insufficient data and limited constraints.

Finally, the solution to the Bongard problem at the beginning of the article: the images on the left depict convex shapes, and the images on the right depict concave shapes.