Exploring biphasic programming: a new approach in language design

I’ve noticed a small but interesting trend in the programming languages space. I’m not sure how novel it is, but this pattern, which I’ll refer to as “biphasic programming,” is characterized by languages and frameworks that enable identical syntax to express computations executed in two distinct phases or environments while maintaining consistent behavior (i.e., semantics) across phases. These phases typically differ temporally (when they run), spatially (where they run), or both.1

“Biphasic programming” is a term I’ve coined, but I feel like it helps capture the essence of several languages. What’s interesting to me is how it can be applied to different types of problems. To illustrate the concept, I’ll go through a few examples.

Zig

The first example is Zig. Zig is a systems programming language that lets you write highly performant code with relatively easy incremental adoption into C/C++ codebases. One of its main innovations is a fresh approach to metaprogramming called “comptime” which allows you to run ordinary functions at compile time.

What makes comptime unique compared to preprocessing systems and macro systems like those in C, C++, and Rust is that it gives you the same 2 expressivity of the base language through the “comptime” keyword, instead of introducing an entirely separate domain-specific language that only advanced users might want to learn. Here’s a (silly) example from their docs:

const expect = @import("std").testing.expect;

fn fibonacci(index: u32) u32 {

if (index < 2) return index;

return fibonacci(index - 1) + fibonacci(index - 2);

}

test "fibonacci" {

// test fibonacci at run-time

try expect(fibonacci(7) == 13);

// test fibonacci at compile-time

try comptime expect(fibonacci(7) == 13);

}

As a case of biphasic programming, comptime lets Zig users seamlessly switch between running code during build time versus during runtime within their source code in a way that doesn’t introduce a steep learning curve. It shifts the developer’s mental model from thinking of metaprogramming as advanced wizardry to being more of an optimization tool that can also be leveraged to implement generics and other code generation uses. I haven’t had a chance to write many Zig programs yet but the comptime system seems like a clever approach to reduce both compiler complexity and soften the language’s learning curve.

For what it’s worth, compile-time code execution isn’t a brand-new idea. However, Zig’s approach does seem to avoid several drawbacks. For example, unlike Rust and its const functions, Zig doesn’t impose function coloring for comptime functions. Likewise, unlike C++’s templating system, Zig doesn’t introduce any new syntax for representing generics. And compared to Lisps like Scheme and Racket which support hygenic macros, well, Zig doesn’t require everything to be a list.

TL;DR: Zig supports a form of biphasic programming where the same functions can run in either of two distinct phases, which differ temporally (build time vs runtime) and spatially (on the build system vs on the machine running the binary).

React Server Components

The second example of biphasic programming I’ve noticed is React Server Components (RSC). React isn’t a language of its own, but as a JavaScript web framework, it has quite a sizeable mindshare as a foundational system for writing and composing UI components and their associated UI logic for large websites. Lately, the front-end JavaScript ecosystem has been doing a lot of exploration to figure out how to most efficiently render UI components on either the server or client to improve page performance. Many solutions have been proposed, and one of the most ambitious is RSC.

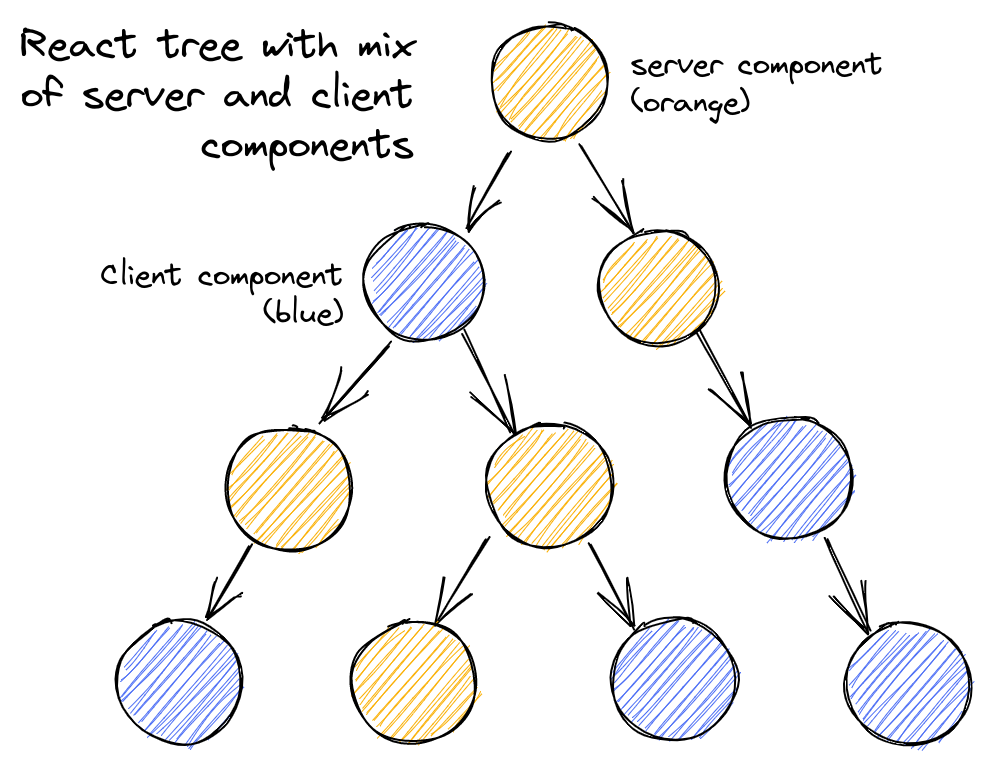

The idea behind RSC is to allow a React component to specify whether it should be rendered on the server side or the client side and to allow such components to be composed together freely. For example, a Feed component might be rendered on the server (as it needs to fetch the list of feed items from the database), while each child FeedItem can be rendered on the client (as they’re pure functions of the item state), while a FeedItemPreview may be rendered on the server (since it needs to fetch the item’s content from the database). The developer can choose which components should be calculated where, and the underlying engine (usually a JavaScript bundler that produces both server-side code and client-side code) optimizes everything so that components are rendered on the server or client when needed, minimizing the amount of dynamic HTML and component information shipped back and forth.

This is just my rough understanding of RSC. From what I’ve heard, getting this all working and stabilized is still a massive work in progress. But I think the paradigm is a curious example of biphasic programming. There are many ways one could go about reducing the amount of code that needs to be shipped and executed on a client browser and offloading more work onto the server, but most existing solutions today require developers to treat React components as a pure client-side abstraction, or as a pure server-side abstraction. For example, either an entire page is rendered on the server, or an entire page is rendered on the client, and vice versa. Taking the React component model and letting the developer switch where a component should be rendered feels like it could be a powerful abstraction if the engine can be optimized enough and if the generated code can be made sufficiently debuggable.

TL;DR: React Server Components promises a form of biphasic programming where the same JavaScript + JSX syntax can be used to represent components that are rendered on the server or client and can be flexibly composed. Server-side and client-side rendering operate at the same time, but they differ spatially (on the server vs on your browser).

I also want to give an honorable mention to Electric Clojure, a project I discovered at a lightning talk its creator gave at Systems Distributed which applies a similar idea to offer strong composition over the frontend/backend boundary, but using the Clojure language. I’m not familiar enough with it to cover it in detail, but I’ve included a screenshot from their repo that hopefully suggests how it parallels React Server Components.

Winglang

A large part of the reason I’ve been so curious about this “biphasic programming” idea is that for the past two years, I’ve been working on Winglang, a new programming language for writing cloud applications, which embraces this concept pretty heavily in its design. This project is the most nascent of the three examples I’m covering (it’s only been in development for two years), but for this post I’m going to try and keep the introduction as short possible to give just enough context for its biphasic type system.

The gist behind Winglang is that thanks to the availability of vast amounts of compute, major cloud providers like AWS, Azure, and GCP have been able to provide developers with a variety of scalable, high-level services like queues, pub-sub topics, workflows, streams, storage buckets, etc. Colloquially, these are often called resources. Infrastructure-as-code tools like Terraform and CloudFormation make it possible to manage these resources with JSON or YAML.

In principle, it shouldn’t be hard build complex applications with these resources. But if your application large enough and has many resources, it can become error-prone explicitly wiring up every single serverless function or container service with the permissions and configuration of its required resources. It’s also difficult to design custom interfaces around these resources.

Winglang aims to let you write libraries and applications that compose both infrastructure resources and application logic together, through what the language calls preflight and inflight code. Here’s an example program to demonstrate:3

// Import some libraries.

bring s3;

bring lambda;

bring redis;

bring triggers;

// Define our abstraction.

class Cache {

_redis: redis.Redis;

_bucket: s3.Bucket;

new() {

this._redis = new redis.Redis();

this._bucket = new s3.Bucket();

}

pub inflight get(key: str): str {

// Check Redis first, otherwise fall back to S3

let var value = this._redis.get(key);

if value == nil {

value = this._bucket.getObject(key);

this._redis.set(key, value!);

}

return value!;

}

pub inflight set(key: str, value: str) {

// Update S3 and redis with the new entry

this._bucket.putObject(key, value);

this._redis.set(key, value);

}

pub inflight reset() {

this._redis.flush();

this._bucket.empty();

}

}

let cache = new Cache();

// Empty the cache once an hour.

let schedule = new triggers.Schedule(rate: 1h);

schedule.onTick(inflight () => {

cache.reset();

});

// Create an AWS Lambda function to do some fake business logic.

let fn = new lambda.Function(inflight (key) => {

let value = cache.get(key!);

return "Found value: " + value;

});

// Publish the function to a public URL.

fn.expose();

At the top-level scope of the program, all code is preflight. Among other things, we can define classes, instantiate resources, and call preflight functions (like onTick() and expose()) to augment and create infrastructure. These statements are executed at compile time. But wherever the inflight keyword is used, we’re introducing a scope for code that can only run once the application is deployed to the cloud. get(), set(), and reset() are all inflight functions.

The Winglang compiler enforces several phase-related invariants. For example, inflight functions can reference data from preflight, but they can’t call preflight functions, since doing so could modify your graph of resources. Likewise, preflight functions can’t run inflight functions, but they can convert inflight functions into bundled JavaScript. (Yes, Winglang relies on JavaScript as its underlying runtime).4 But despite these rules, preflight code and inflight code are otherwise grounded in the same syntax. Both provide access to the same language facilities like variables, for loops, structs, strings, arrays, classes, and so on.

It’s possible to draw parallels between Winglang’s preflight/inflight distinction and Zig’s comptime/runtime distinction. But it’s probably no surprise that since the languages have been built around different use cases, they’ve ended up with pretty different designs. For example, Zig’s comptime aims to avoid all potential side effects, while Winglang’s preflight encourages side effects so you can mutate your infrastructure graph.

TL;DR: Wing offers a form of biphasic programming where code can be executed for defining cloud infrastructure, or for interacting interacting with cloud infrastructure. These two phases, called preflight and inflight, differ temporally (compile time vs runtime) and spatially (preflight runs on the build system while inflight code may be executed on any compute system that supports a JavaScript runtime).

So what?

One takeaway is that this biphasic programming thing can be used to solve a lot of different problems. In Zig, it makes it easy for people to do compile-time metaprogramming. In React, it makes it possible to write more specialized and optimized frontend apps. In Wing, it lets you model the infrastructure and application concerns of a distributed program. That’s pretty cool!

But there’s likely more to explore here - like how the rules of these biphasic solutions overlap or differ. In Zig, every function that you can run at comptime is also safe to run at runtime - so we can say there’s a subset relationship between what functions can be run at comptime and which can be run at runtime. The same applies to React Server Components - any component that you can render on the client can also be rendered on the server. But in Wing, the two phases of preflight and inflight are strictly separate, so to represent code that can run in either phase, you’d need a separate label for these functions (like “unphased functions”).

Another open question is understanding to what degree biphasic programming represents capabilities that can’t be expressed in normal languages. Zig needed a new keyword for this comptime thing - but are there other existing languages that let you do this, perhaps in userland? Does providing it as a dedicated language feature provide any improved safety or error handling?

-

One can say that metaprogramming systems are related to biphasic programming. For example, C pre-processing can be thought of as biphasic programming in spirit since it allows you to run code in the pre-processor, a phase of compilation before runtime. But it doesn’t satisfy the definition I’ve provided since the preprocessor only does textual substitutions, and C’s preprocessor macros are limited – #ifdef is quite different from a bona fide if statement. Lisp-style hygenic macros like those in Scheme and Racket, on the other hand, are expressed through functions that support the same expressiveness as the base language(s), so I think it would be fair to say Lisps provide some of the oldest examples of biphasic programming. ↩

-

According to the Zig docs, comptime expressions are limited in some ways – for example, they can’t call external functions, include

returnortryexpressions, or perform side effects. However, a large fraction of the language is available, and the included example shows that comptime functions don’t need to be explicitly labeled as such, which helps make the feature feel more ordinary. ↩ -

To simplify the example, I’m using some APIs that don’t exist in Winglang today – for example, if you want to use S3, Winglang instead provides a

cloudmodule with classes that can compile to either AWS or other clouds. But I don’t want to complicate the example with the whole dependency injection idea so let’s just pretend there’s ans3module. ↩ -

JavaScript ain’t the fastest language, but it’s reliable and has a broad ecosystem. We’re interested in supporting other languages for inflight as well in the future. ↩